Tathagata Basu

Lead, Knowledge Management

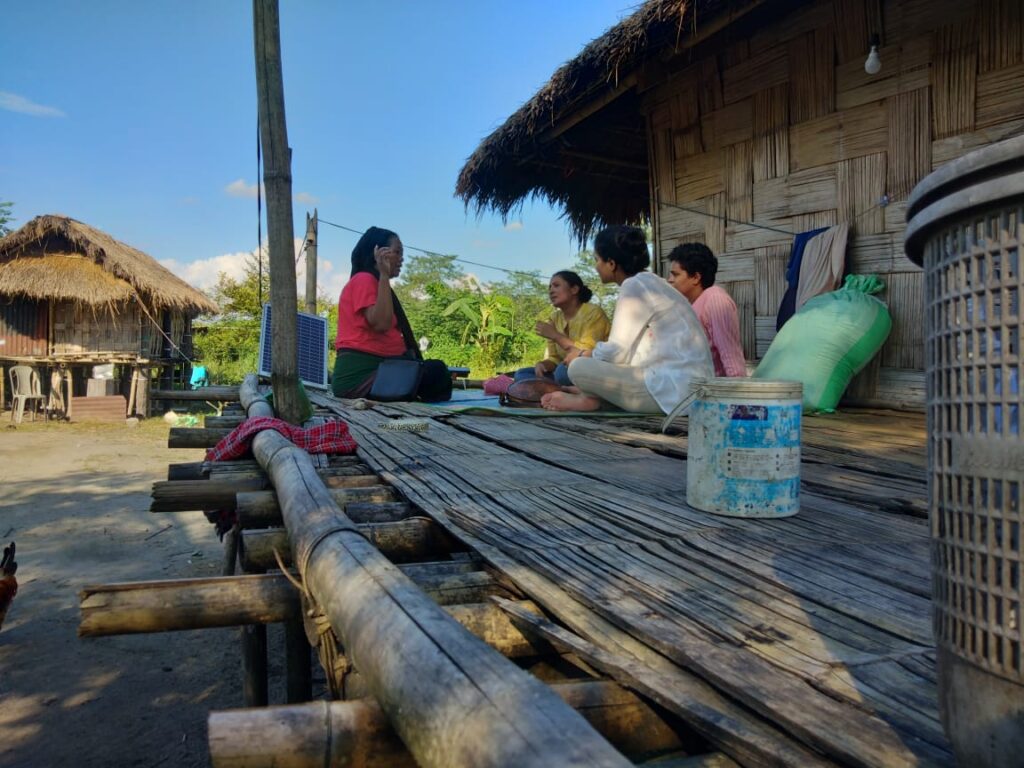

It was a warm Monday evening at Arun and Nina Gao’s (name changed) home in a remote picturesque village in Lower Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh. Arun had recently quit the job in the city and returned home to spend more time with his family. Nina worked at the nearby Primary Health Centre (PHC). Arun now worked as a contractual farm labourer from time to time.

Their son, Kishore, was brewing tea and chatting with them about the future of children. Nina started preparing dinner and Arun got back to making the charpai he was working on for the last few days. Suddenly, Nina heard their daughter Rupali’s screams and ran only to find Arun lying on the floor. He was conscious but unable to move. Kishore rushed to get help from the doctor at the PHC who lived nearby. He examined Arun, gave some medicine, and said that he should be taken to Dibrugarh for further treatment immediately. The doctor called the village boatman but learnt that he was in Dibrugarh for some work. To the family’s great despair, they realized that there was nothing they could do but wait till morning. The nice and warm tea-time gave way to a night of extreme distress.

They rushed to the riverside early next morning. But crossing the river was only the first step. They booked a private vehicle and reached the hospital in Dibrugarh. Miraculously, Arun was hanging in there albeit with difficulty. Within half an hour of reaching the hospital, Arun was no more. Nina was bereaved that they could not offer him the treatment he sorely needed.

Nina struggled to hold back her tears while sharing her about her loss with us. She kept wondering what could have saved her ‘bura’. “He should have continued his job in the city! We all should have moved to Dibrugarh when our son went to study there! I should have been more regular with my religious rituals!”

We embarked on a quest to learn more about the nature of barriers that makes a tribal person such as Arun lose their life almost 4 years sooner than a non-tribal person in India. As we travelled more than 10,000 km across 5 states with a significant share of tribal populations, we came across many more stories of personal loss. Like Nina, we also wondered what could have saved Arun’s life. Better transport connectivity, certainly. But what else? Maybe a better-equipped PHC could have provided the required treatment? Could an early screening have diagnosed his latent heart condition on time? Would the diagnosis have helped him make necessary lifestyle changes? The answer, we believe, is all of these. And, many more.

We realized the multifaceted and interconnected nature of improving access to healthcare services. The insights we collated through every interaction, of loss and joy both, strengthened our belief that bringing together expertise and efforts was the way to reach the state of Anamaya – the state of being free from suffering for more than 100 million tribal and marginalised people of India.